This report was originally published by Demos.

The notion that all citizens have a voice in our country's governance is at the center of the American ideal of democracy. Yet the role of corporate and private money in our political system means that the voices of the majority are often drowned out by those with the most money. Campaign and committee donations help wealthy interests determine who runs for office and who wins elections. This effect, combined with millions of dollars in lobbying, allows the biggest spenders to shape the country's political agenda and gives them disproportionate influence over the policymaking process. As a result, the minority population of affluent Americans see their priorities reflected in our legislative objectives, even when the majority of the country disagrees with their preferences.1 This problematic political spending entrenches economic inequality and political power in a system where legitimacy hinges on equality and self-determination. Under this regime the economic advantages held by companies like Walmart can be leveraged to yield legislative returns. The political spending of big retailers reveals how extreme disparity not only subverts our economic promise; it undermines our democratic principles and our government's commitment to the public good.

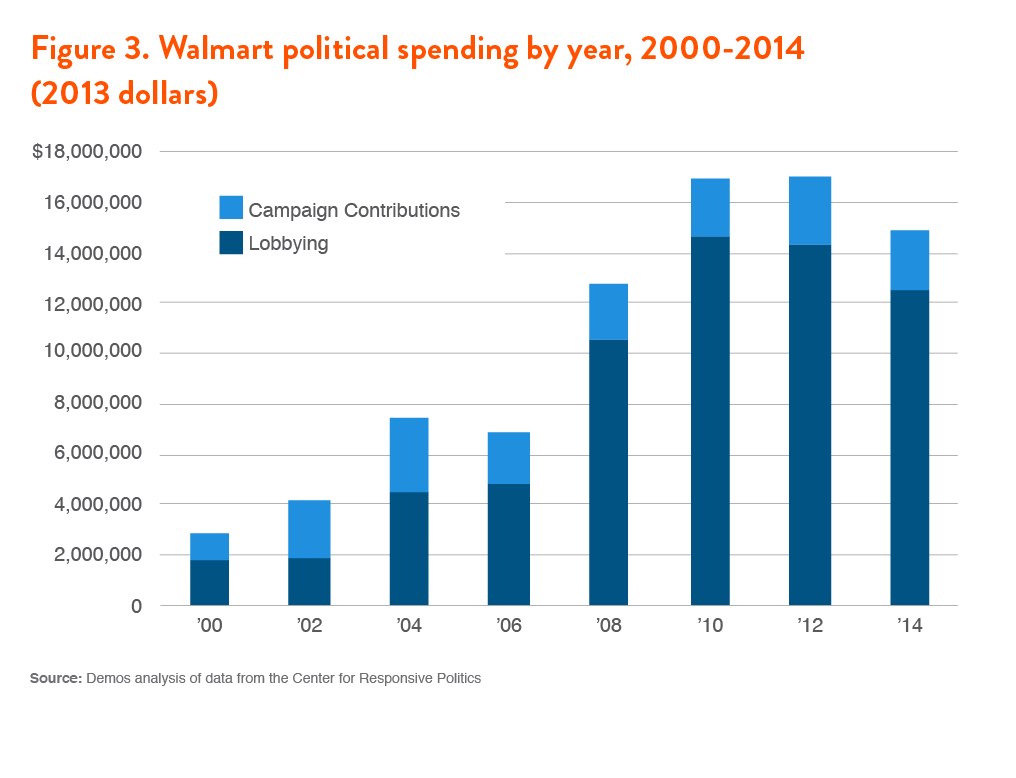

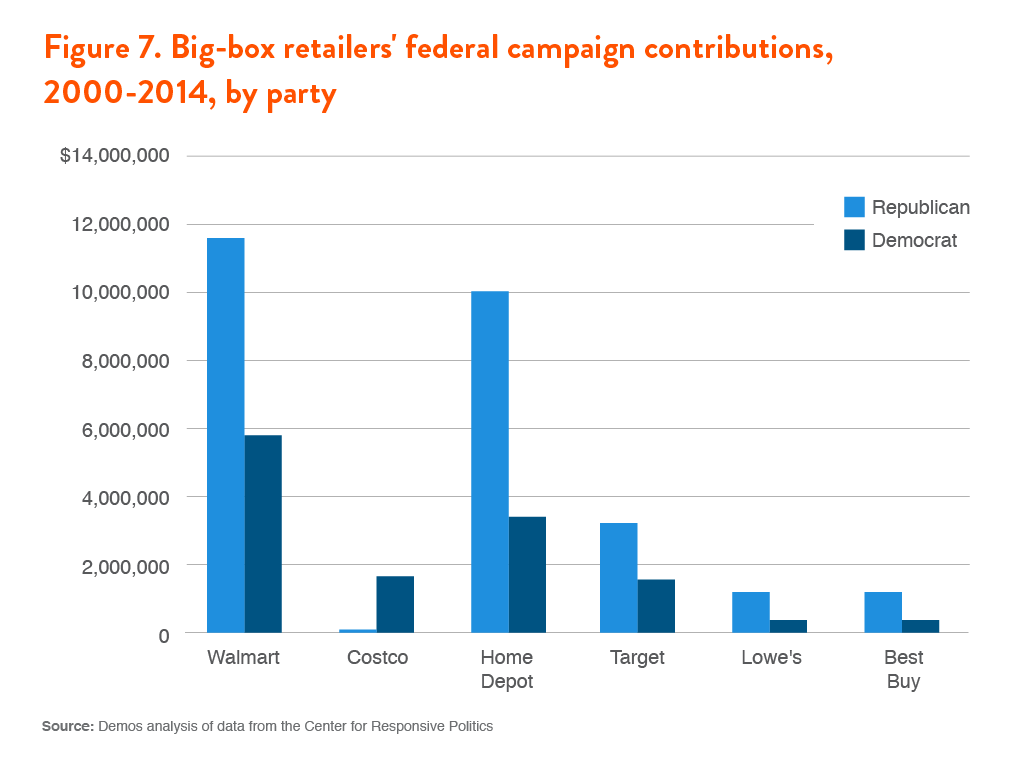

In this report we examine the federal election spending of the six big-box retail companies with earnings ranked among the top retail companies in the country, using newly available data from the Center for Responsive Politics. We find that their reach is pervasive, reflected in enormous and growing expenditures to influence electoral and policy outcomes. Among this group, Walmart is the biggest spender by a wide margin, with $2.4 million in donations through its Political Action Committee (PAC) and individual donations and $12.5 million in lobbying expenses during the 2014 electoral cycle-spending about three times more than its nearest rival, Home Depot. This political spending is a problem for democracy, because extensive research suggests that the domination of wealth in our electoral process can significantly affect public policy, and that the priorities of the affluent often diverge from majority opinion.2 On issues like taxation, economic regulation, Social Security, and the minimum wage, the differences can be stark.

Big Retail, Big Money

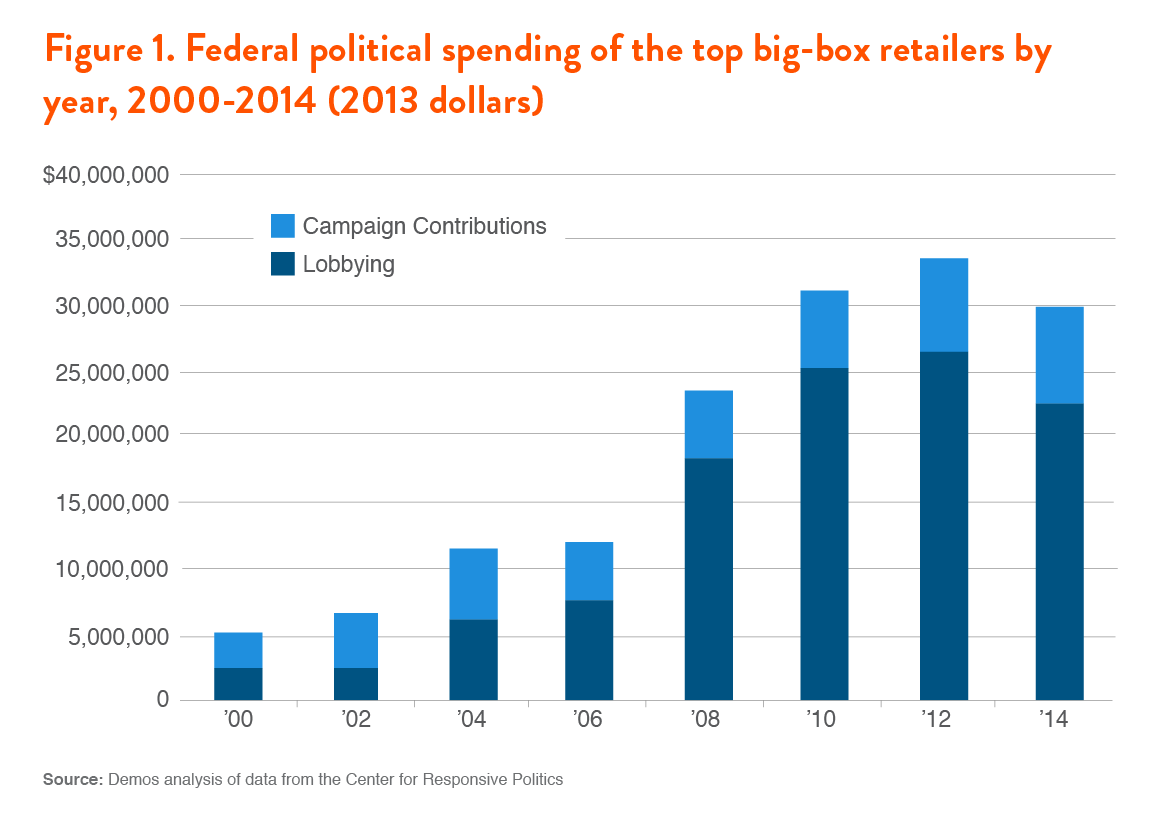

There has been a dramatic mobilization of political power among America's largest big-box retailers over the past four election cycles, with federal campaign and lobbying expenditures growing from $5.2 million during the 2000 political cycle to $29.8 million during the 2014 cycle, an almost six-fold increase. Even that number massively underestimates retail's reach by excluding state and local elections, as well as contributions to 501(c)3 and 501(c)6 groups like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and the Chamber of Commerce. The fastest increases in retail political spending over the period appeared with the 2008 election cycle. Total campaign and lobbying expenditures grew by 95 percent in that cycle, driven by lobbying expenditures that more than doubled. In the 2010 midterm election cycle, lobbying topped $25 million. Political spending by big-box retailers peaked at a total of $33.7 million in 2012-the following presidential election year (see Figure 1).

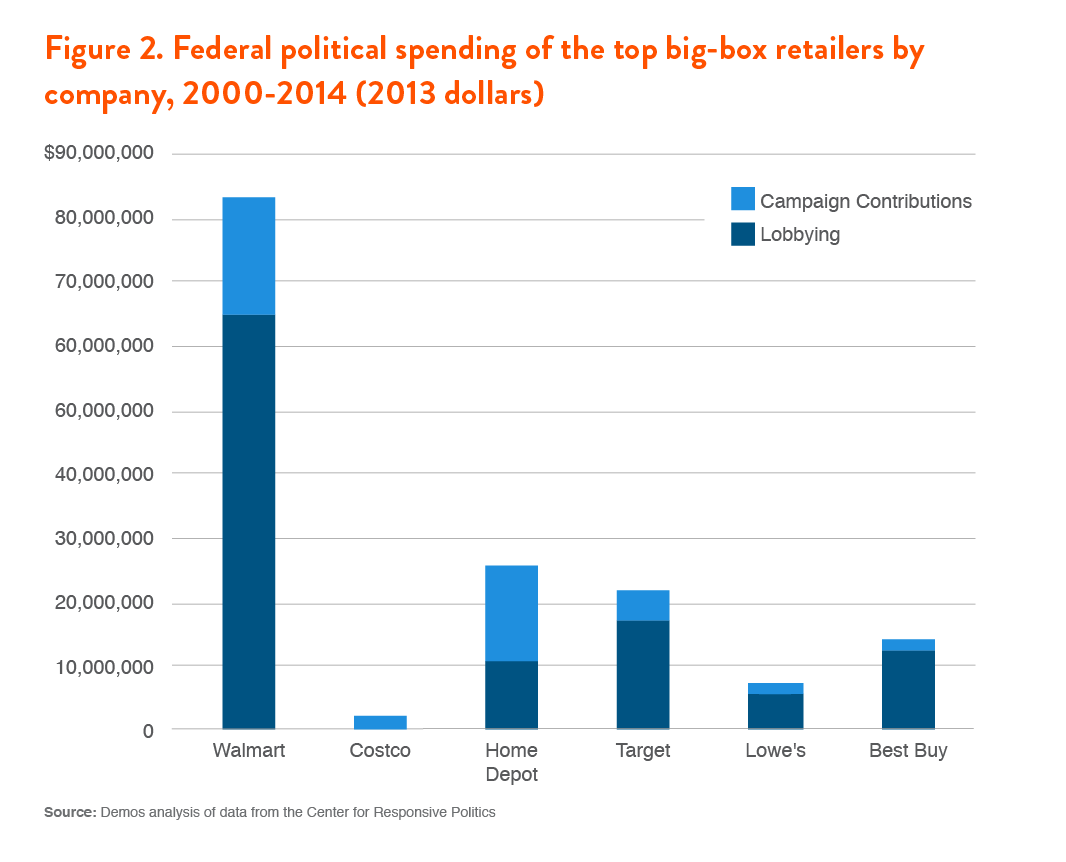

Not all major retailers spend alike, even among the market's most profitable corporate membership. Two retailers from our list-Walmart and Home Depot-are ranked among the top 100 political donors overall for the period since 1989, a level that earns the designation "Heavy Hitters" from the Center for Responsive Politics.3 Target and Best Buy, though not distinguished by campaign contributions, amass enormous federal spending totals through their lobbying efforts. Costco's total federal spending falls at the bottom of the list, with campaign contributions of $2 million over the entire 15-year period and no lobbying expenditures at all (see Figure 2).

The retail firms with the largest federal political spending-like Walmart and Home Depot-exemplify the relationship between economic and democratic inequity. Walmart is the industry's largest political spender as well as the world's largest retailer and private employer, distinctions that give the company considerable influence over labor and product markets in the U.S. and beyond. In markets, Walmart draws upon this economic clout to exacerbate the inequality at the core of its business model. When Walmart comes to town, retail workers see their wages drop and employment growth recede.4 At the same time, the company's $16 billion in annual profits are channeled to a much smaller pool of earners, namely the Walton heirs, who inherited their vast wealth from Walmart founders Sam and Bud Walton and today rank among the richest billionaires in the world. The practices are emblematic of the growing concentration of wealth and income at the top of the U.S. economy, a trend that has been linked to slow growth, rising volatility, and even poor sales performance for companies like Walmart whose revenues depend on consumer spending.5

But markets are not the only institutions that respond to the outsized power of Walmart and companies like it. There is strong evidence that an important impact of campaign contributions is to shape the views of candidates seeking to run viable campaigns and help candidates with friendly policy views win office, in addition to increasing access to politicians with the intent of setting the political agenda.6 Studies of the telecommunications industry show that regulators respond to private political spending with regulations that favor the donors.7 And companies that bid for federal contracts across industries are more likely to be granted those contracts if the bids are complemented by campaign contributions.8 This evidence suggests that political spending provides highly profitable companies like Walmart with the opportunity to influence the conversation in a way that reflects their bottom lines at democracy's expense and to use campaign contributions and lobbying to leverage their economic power into law (see Figure 3).

The Walton Family Goes to Washington

The majority of Walmart's public shares are owned by the Walton family heirs, who have shown a penchant for political engagement. Over recent years, the family has consolidated their ownership in the company and seen their private wealth balloon. Since the beginning of the Great Recession in 2007, the Walton family wealth has grown by 96 percent while the typical American household's net worth fell by 40 percent.9 The spectacular growth of the Walton family's affluence can be linked, in part, to decades of political influence. According to Bloomberg News, the Waltons started lobbying for a repeal of the estate tax in the 1990s, and continue to exploit obscure tax loopholes that protect the assets of the country's richest heirs.10 In a prime example of the revolving door between the private interests of the affluent and policymakers, one Arkansas Congresswoman who supported the repeal of the estate tax and received $83,650 in campaign donations from Walmart works as a lobbyist for the company today.11 In the period since the late 1990s, the Walton family has spent more than half a million dollars on lobbying through its foundation, Walton Enterprises.

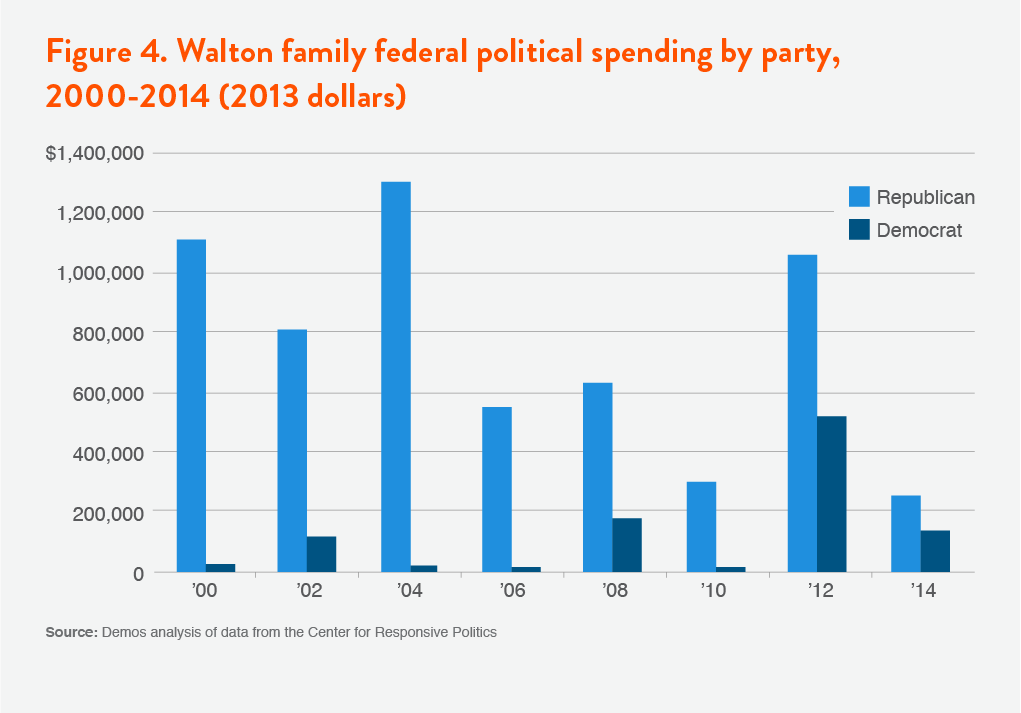

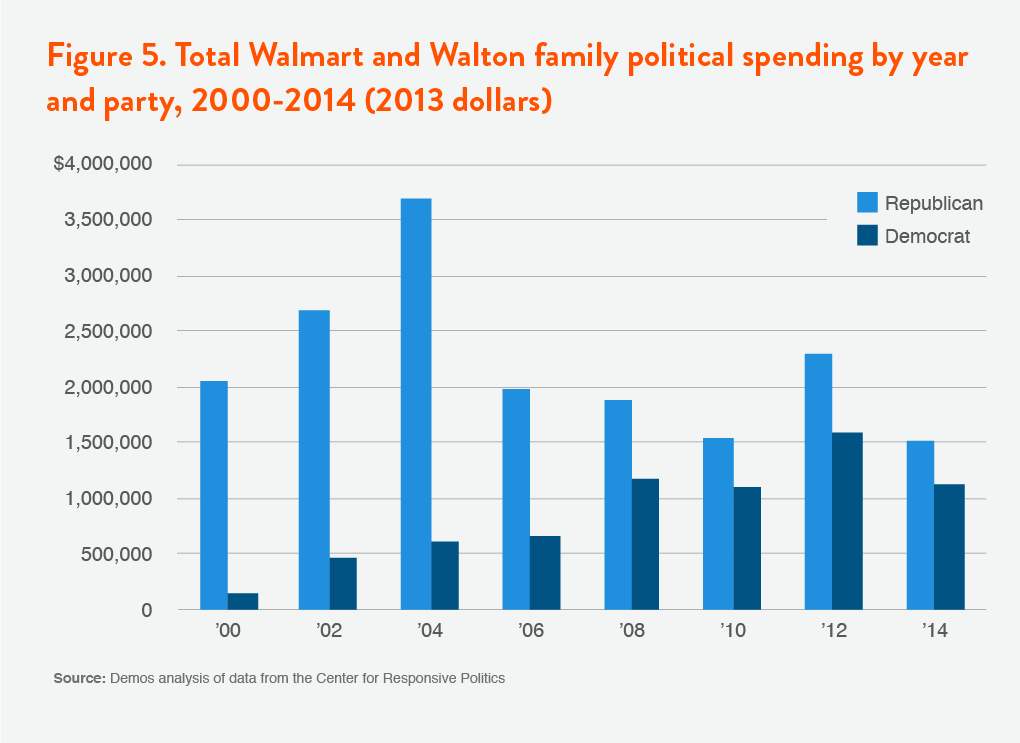

Demos examined Walton family political contributions over the period between 2000 and 2014 and found that the Waltons made a total of $7.3 million in campaign contributions over the period, with greater total contributions in presidential election years (see Figure 4). The Waltons achieve broad access by contributing to both parties, but their spending heavily favors Republican candidates and PACs. Since 2000, Walton family campaign contributions included $6 million to Republican candidates and PACs, $1 million to Democrats, and $236,085 to independent or non-affiliated candidates. These numbers reveal a savvy investment in their political interests, but still far understate Walton family's influence through other means. For example the Walton Family Foundation-not included in our calculations here-is one of the biggest education funders in the country, with an emphasis on supporting the privatization of K-12 education.12 Their use of private lobbyists and spending at the state and local levels is also not included in our calculations.

Big-box Retail's Biases

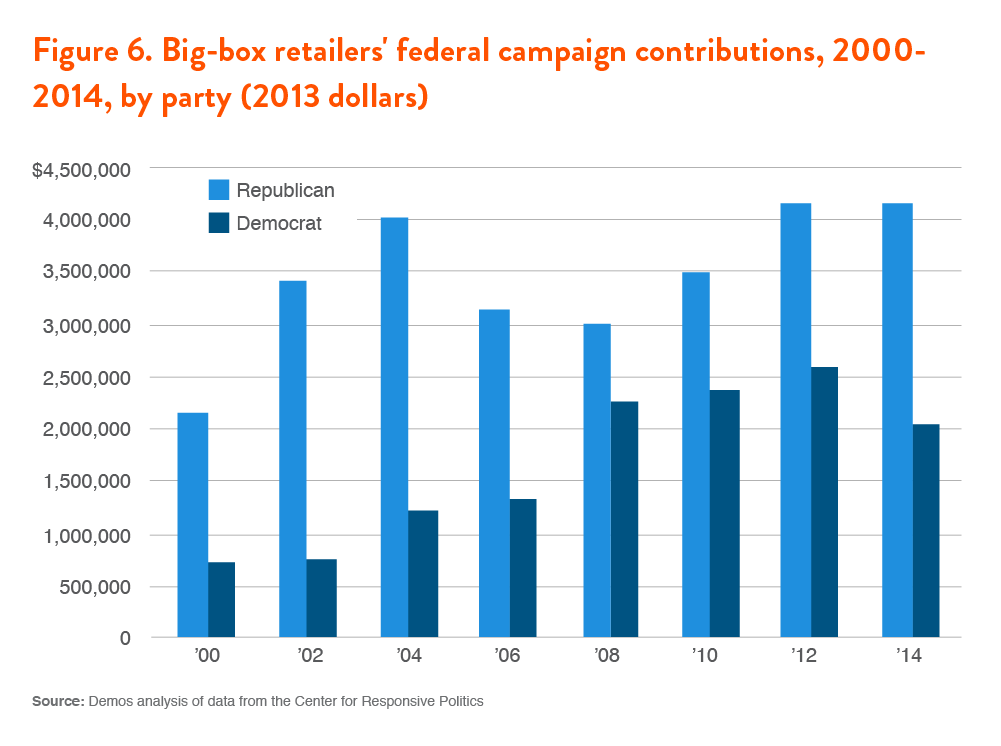

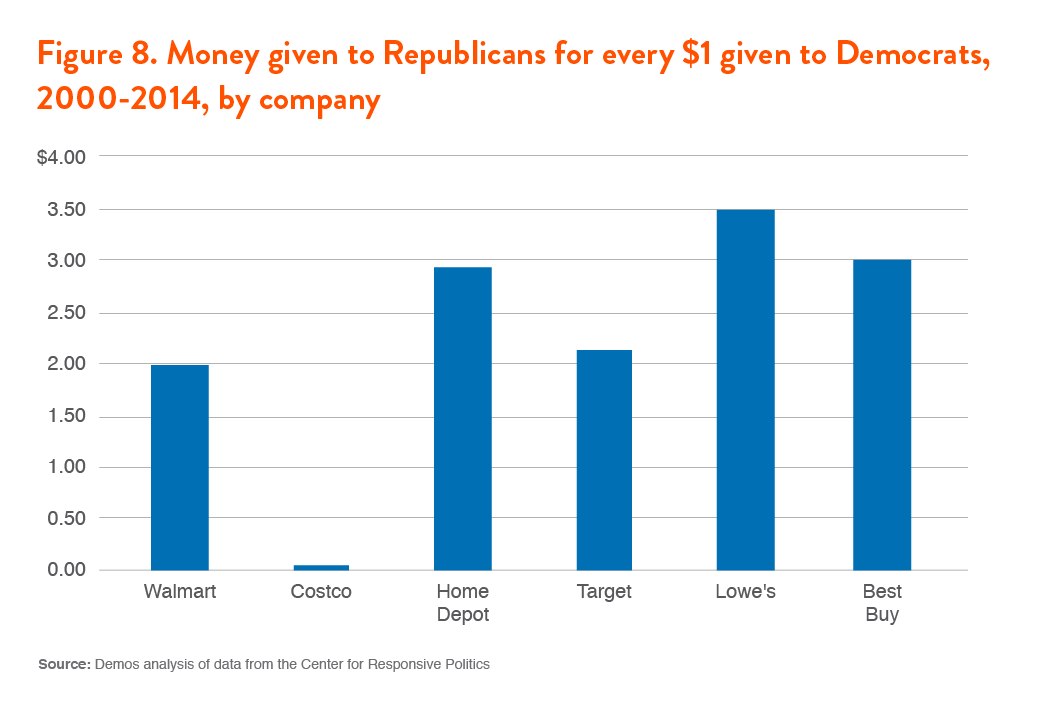

Although retail political spending is both deep and broad, retailers overwhelmingly support Republicans over Democrats. Since 2000, the country's largest big-box retailers donated to Republicans over Democrats by a margin of more than 2-to-1 (see Figure 6 & 7). Walmart-which donated to a total of 295 different candidates in the most recent election cycle-gave $1 to Democrats for every $2 donated to Republican campaigns or PACs (see Figure 8). That compares to even greater Republican leanings at Target, Home Depot, Best Buy, and Lowe's, which gave $2.14, $2.95, $3.03, and $3.50 to Republicans for every $1 to Democrats, respectively. Costco was the only company that had a strong Democratic preference, allocating just $0.04 to Republicans for every $1 in Democratic spending. But since Costco's total spending was far lower than other retailers, its donations to Democrats over the period still amounted to less than those of big spenders Walmart and Home Depot, despite their biases.

This is unsurprising-Republicans are often seen as the party of big business. Over the last two years, House Republicans have unanimously voted against raising the minimum wage and attempted to eliminate Davis-Bacon protections.13 At the same time, they fought to extend the Bush Tax Cuts and made 50 attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act.14 The Senate has taken similar stands on behalf of corporate interests: all Republicans but one signed onto a bill to stop new NLRB rules and all but one voted against the Buffet rule that would ensure that the wealthiest one percent pay a 30-percent income tax rate.15

The influence of wealthy corporate donors has concrete results. Research suggests that campaign contributions like those examined here can significantly affect policy. For example, a recent article in the National Tax Journal finds that increases in business campaign contributions lead to lower state corporate taxes.16 This outcome exacerbates inequities because companies like Walmart rely on a business model that depends on tax payers to support their low-wage workforce, while simultaneously aiming their political spending to reduce their own tax burdens.17 Congressional votes to hold down the value of the minimum wage are another example. Polls consistently show that a majority of American voters favor raising the minimum wage. But while 78 percent of the general public favors a minimum that would bring full time workers and their families above the poverty line, only 40 percent of wealthy Americans agree.18 Organizations representing the minority opinion, like the Chamber of Commerce, have spent tens of millions of dollars to advance their position in legislatures.19 And policymakers have allowed the real value of the federal minimum wage to erode for the past five years.

Retail's Insider Access

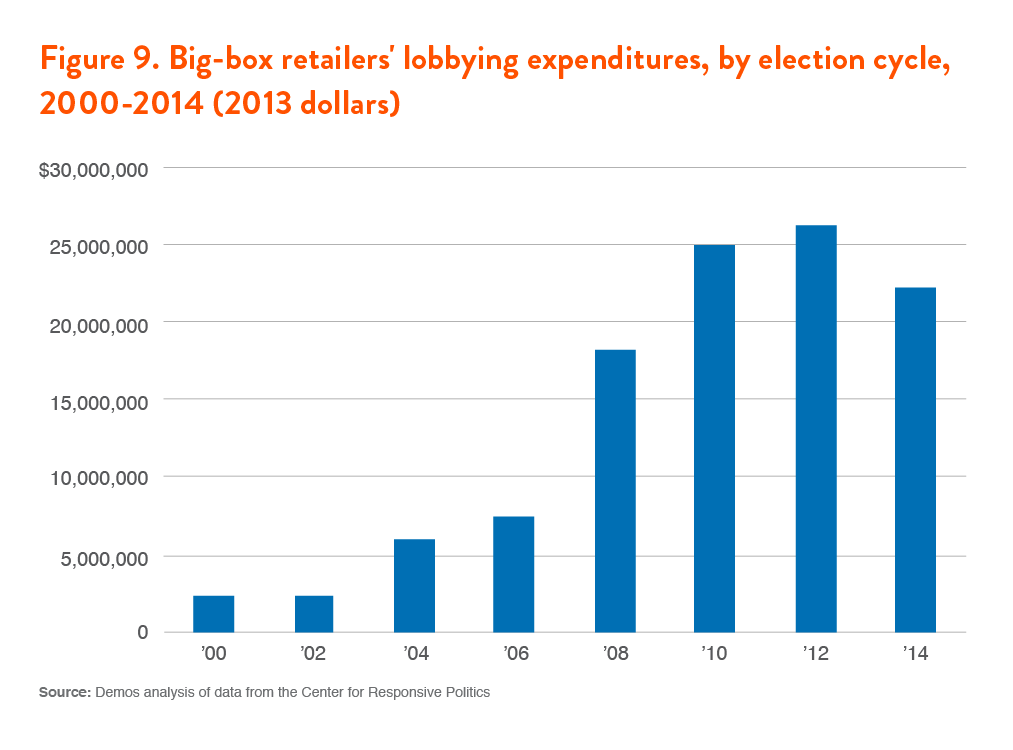

With the exception of Costco, all of the country's largest big-box retailers spend significant and growing amounts of money on lobbying. Over the period studied, the companies spent a total of $111 million lobbying congress on various bills.20 This avenue of spending has grown considerably in recent election cycles, from $2.3 million in 2000 to a peak of $26.5 million in the 2012 election cycle (see Figure 9).

Retailers lobby on a variety of issues, including tax policy, labor issues, and the terms of international trade.21 A vast literature shows that these efforts produce returns, often at the expense of other democratic interests.22 In a comprehensive study of such conflicts, researchers found that business interests prevailed in 9 out of 11 issues in which businesses and labor were opposed.23 The ability of companies to win policy outcomes through massive spending on behalf of their financial interests is problematic for a Congress charged with serving the people.

Taxes were the most frequently lobbied issue by big-box retailers in 2014 by a large margin. This legislative area has proven lucrative for business in the past-experts in corporate strategy research show that a 1 percent increase in businesses lobbying expenditures yields a lower effective tax rate of between 0.5 and 1.6 percent for the firm.24 One study on the subject finds that the market value of an additional dollar spent on lobbying could be as high as $200.25 In 2014, the largest big-box retailers reported lobbying on a total of 37 incidences of specific taxation, including corporate tax reform, internet sales tax, and the extension of temporary tax breaks. The next most common issues of lobbying were health care reform, labor, antitrust, and workplace regulations.

Conclusion

Campaign spending and lobbying by moneyed interests is not new to American politics, but it has expanded significantly over the past 15 years. The total political spending of the country's largest big-box retailers grew 6 times over in the years from 2000 to 2014-reaching almost $30 million in the 2014 cycle. These companies and their wealthy owners have increasingly used their massive profits to lobby against the interests of their own workforce and to reduce their responsibility for sustaining the economic system from which they prosper. Accounting for this outsized spending is important because evidence shows that when the priorities of the affluent diverge from majority opinion, policy reflects the preferences of the donor class. Big-box retailers have expressed their preferences emphatically on both sides of the aisle concerning issues like taxation, health care coverage, and unionization rights.

The political spending at retail's largest companies exemplifies the relationship between economic and democratic inequity. Walmart, in particular, stands out as one of the top political donors in the entire country and the largest retail corporate political spender. Federal political spending by Walmart and the company's wealthy family heirs embeds the economic disparity at the heart of their low-wage business model into the democratic system.

New policies to mitigate the disproportionate political influence of the affluent minority are a critical step toward a stronger democracy and an economy that works for more than just the wealthy few. A federal matching system for small donations would amplify the voices currently drowned out by big donors, and provide an incentive for candidates to give greater attention to citizens who cannot afford to spend millions of dollars in order to be heard. Research suggests that such programs increase the racial and economic diversity of donors.26 Alternatively, publicly funding elections would protect candidates from floods of corporate and private spending by wealthy donors, and from their disproportionate influence over campaigns. Finally, research suggests that lobbying regulations lead legislators to weigh citizens' opinions more equally.27 Since lobbying expenditures were an important factor in the rise of big-box retailers' political spending, responsible oversight of this spending is crucial to ensuring that all Americans have an equal voice. It is time to tell retailers that democracy is not for sale.

-------------

Methodology

Measures of political spending require compilation of multiple data sources. This report draws from data secured by the Center for Responsive Politics. Open Secrets provided data on the political spending of Walton family members from 2000 to 2014. On their website, OpenSecrets.org, lobbying data are available by company and PAC and campaign spending are available by company, PAC, and individuals. This report adds contiguous years together to examine expenditures over an election cycle. Elections spending data for 2014 are incomplete and thus understate annual spending in that year. The retailer data were collected during the week of November 3, 2014. The Walton family data were collected during the week of September 8, 2014.

The data in this report does not include Walton family spending through their foundations or lobbying, nor state and local spending for any retailers nor the Walton family. These data do not include the money that companies spend on industry groups (501(c)6s) like the Chamber of Commerce. As a result, even the large numbers we present represent only a portion of the retail and Walton family influence over the political system. Our numbers are inflation-adjusted to 2013 dollars, except for 2014 data.

Endnotes

- Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page, "Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens." Perspectives on Politics, Vol 12, No. 3, (September 2014) pp. 564-581, available at:http://journals.cambridge.org/download.php?file=%2FPPS%2FPPS12_03%2FS153...

- Including Larry Bartels, Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008); Martin Gilens,Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012); Benjamin I. Page, Larry M. Bartels, and Jason Seawright, "Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans," Perspectives on Politics 11:1 (2013), pp. 51-73; and Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page, "Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens." Perspectives on Politics,Vol 12, No. 3, (September 2014) pp. 564-581.

- Open Secrets, "Heavy Hitters: Top All-Time Donors, 1989-2014," Center for Responsive Politics (October 9, 2014), available at: https://www.opensecrets.org/orgs/list.php.

- David Neumark, Junfu Zhang and Stephen Ciccarella, "The Effects of Wal-Mart on Local Labor Markets," NBER (2005), available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w11782; David Neumark, Junfu Zhang and Stephen Ciccarella, "The Effects of Wal-Mart on Local Labor Markets," IZA Discussion Paper No. 2545 (January 2007), available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=958704##; Arindrajit Dube, T. William Lester and Barry Eidlin, "A Downward Push: The Impact of Wal-Mart Stores on Retail Wages and Benefits," UC Berkeley Labor Center (December 2007), available at:http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/a-downward-push-the-impact-of-wal-mart-s...

- Jonathan D. Ostry, Andrew Berg, and Charalambos G. Tsangarides, "Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth," IMF, (February 2012), available at:http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2014/sdn1402.pdf, Joe Maguire, "How Increasing Income Inequality Is Dampening U.S. Economic Growth, And Possible Ways To Change The Tide," S&P (August 2014), available at: https://www.globalcreditportal.com/ratingsdirect/renderArticle.do?articl..., Ellen Zentner and Paula Campbell, "Inequality and Consumption," Morgan Stanley (September 2014), available at: http://taxprof.typepad.com/files/morgan-stanley-inequality-9-14.pdf.

- Joshua L. Kalla and David E. Broockman, "Congressional Officials Grant Access to Individuals Because They Have Contributed to Campaigns: A Randomized Field Experiment," (March 2014), available at: http://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~broockma/kalla_broockman_donor_access_field....

- Rui J. de Figueiredo and Geoff Edwards, "Does Private Money Buy Public Policy? Campaign Contributions and Regulatory Outcomes in Telecommunications," UC Berkeley (2005), available at:http://bcep.haas.berkeley.edu/papers/Figueiredo_Edwards.pdf.

- Christopher Witko, "Campaign Contributions, Access, and Government Contracting,"Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory (September 2011), available at: http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/03/18/jopart.mur005.a...

- The Federal Reserve, "2013 Survey of Consumer Finances Historical Tables Based on Public Data," (2013), http://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/scf/scfindex.htm;Josh Bivens, "Walton Family Net worth Is a Case Study Why Growing Wealth Concentration Isn't Just an Academic Worry," Economic Policy Institute (October 2013), available at: http://www.epi.org/blog/walton-family-net-worth-case-study-growing/.

- Zachary R. Mider, "How Wal-Mart's Waltons Maintain Their Billionaire Fortune,"Bloomberg (September 2013), available at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-12/how-wal-mart-s-waltons-maintain...

- Ibid.

- Motoko Rich, "A Walmart Fortune, Spreading Charter Schools," New York Times (April 25, 2014), available at: www.nytimes.com/2014/04/26/us/a-walmart-fortune-spreading-charter-school...

- AFL-CIO, "Legislative Voting Records," available at:http://www.aflcio.org/Legislation-and-Politics/Legislative-Voting-Records.

- Ed O'Keefe, "The House has voted 54 times in four years on Obamacare. Here's the full list." Washington Post, (March 21, 2014), available at:http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-fix/wp/2014/03/21/the-house-has-....

- AFL-CIO, "Legislative Voting Records," available at:http://www.aflcio.org/Legislation-and-Politics/Legislative-Voting-Records.

- Robert S. Chirinko and Daniel J. Wilson, "Can Lower Tax Rates Be Bought? Business Rent-Seeking and Tax Competition Among U.S. States," National Tax Journal, December 2010, 63 (4, Part 2), 967–994, available at:http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/economists/daniel-wilson/NTJ-busi....

- U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce, "The Low-Wage Drag on Our Economy," (May 2013), available at:http://democrats.edworkforce.house.gov/sites/democrats.edworkforce.house...

- Benjamin I. Page, Larry M. Bartels, and Jason Seawright, "Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans," Perspectives on Politics 11:1 (2013), pp. 51-73, available at: http://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/~jnd260/cab/CAB2012%20-%20Page1.pdf.

- Open Secrets, "US Chamber of Commerce," Center for Responsive Politics, available at: https://www.opensecrets.org/outsidespending/detail.php?cmte=C90013145&cy...

- It is not odd that lobbying dwarfs campaign spending. A comprehensive literature review on the question by John M. de Figueiredo and Brian Kelleher Richter finds that, "lobbying expenditures remained approximately five times interest group campaign finance contributions." John M. de Figueiredo and Brian Kelleher Richter, "Advancing the Empirical Research on Lobbying," NBER (December 2013), available at: http://papers.nber.org/tmp/13020-w19698.pdf.

- For Wal-Mart lobbying issues, see: Open Secrets, "Wal-Mart Stores," Center for Responsive Politics, available at:https://www.opensecrets.org/lobby/clientissues.php?id=D000000367&year=20...

- John M. de Figueiredo and Brian Kelleher Richter, "Advancing the Empirical Research on Lobbying," NBER (December 2013), available at: http://papers.nber.org/tmp/13020-w19698.pdf.

- Frank R. Baumgartner, Jeffrey M. Berry, Marie Hojnacki, David C. Kimball and Beth L. Leech, Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why, University of Chicago Press (Spring 2009), available at:http://www.unc.edu/~fbaum/books/lobby/Advocacy_July_19_2008.pdf.

- Brian Kelleher Richter, Krislert Samphantharak and Jeffrey F. Timmons, "Lobbying and Taxes," American Journal of Political Science, (October 2008) Vol. 53, Issue 4. p. 893-909, available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1082146.

- Matthew D. Hill, G. Wayne Kelly, and Robert A. Van Ness, "Determinants and Effects of Corporate Lobbying," available at: http://faculty.bus.olemiss.edu/rvanness/Working%20Papers/Lobbying.pdf.

- Michael J. Malbin, Peter W. Brusoe, and Brendan Glavin, "Small Donors, Big Democracy: New York City's Matching Funds as a Model for the Nation and States," Election Law Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 (2012), available at:http://www.cfinst.org/pdf/state/NYC-as-a-Model_ELJ_As-Published_March201...

- Patrick Flavin, "Lobbying Regulations and Political Equality in the American States," APSA 2014 Annual Meeting Paper (2014), available at:http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2454295.